The world of technology hit London’s West End in September 1994 when, for the first time, people could walk into a café, pick up their email and ‘surf the net’ for only £2.50 per hour.

The physical and virtual worlds have been converging ever since, and purchases of physical goods have increasingly migrated to virtual shops. This has led to a rapid shift in the allocation of high-street space – from fashion and homeware stores to coffee shops, restaurants, gyms and beauty salons – everything that you actually need to bring your body to use.

The West End is not immune to this shift. Its shopping districts have already changed to meet the challenges, and will need to continue changing to avoid becoming retail dinosaurs in a technological world. Technology also offers many opportunities to those who can take advantage of them, both for customer delivery and in making the most of precious real-world space – something that planners are also going to have to adopt.

The changing face of retail

Although macro trends bode well for the West End, the counter trend is that fashion stores and footwear have the most to worry about from the internet. The age group most likely to come to work in the West End – as more companies follow Facebook and open downtown HQs – will be 25–35s, closely followed by 18–24s (due to university expansion in the area). These two age groups are native online shoppers.

There are some signs that a high-end reputation and an innovative approach to digital luxury offer protection from online threats. ‘New luxury’ means combining and streamlining on- and offline channels.

The execution of this strategy will make or break the famous West End stores, as Click and Collect is forecast to account for over 40 per cent of luxury fashion sales by 2017.

Selfridges has invested over £300m on its Oxford Street flagship, creating a luxury service and making its Click and Collect foyer more glamorous than the entrance to Claridge’s. Selfridges’s app is top-notch, and its stock management, which underpins the service, is as high-defi- nition as its amazing TVs. If something doesn’t fit, it’s no problem:

a replacement will be brought from the appropriate floor in no time. Profits are up and the transition to digital luxury is on the way.

Another model is Nike’s flagship, which landed at Oxford Circus in 1999. Its shop-as-marketing-tool-never-mind-the-density concept blew all our provincial retail minds away. Not concerned about profits, Nike’s idea for a store was just to amaze the customers – a precursor of the immersive shop-as-media experience that Apple has since perfected.

To counter the channel shift for physical goods, Nike is aiming

to reach the inner designer within all of us. Their DIY sneaker design station is proving a strong driver for young sneakeristas, who will brave Saturday crowds for the opportunity to make their own pair just a fraction different.

The space is attractive but it is also the range that matters – Nike Oxford Street is the biggest European store selling Nike’s full range and attracts tourists from Moscow to Lisbon. Customers can get complete gait analysis and personal recommendations based on individual running style, adding extra reasons to visit in person rather than click.

With online competition closing in on fashion as a whole, there is

no room for shoddy service, less than super-knowledgeable sales assis- tants, or poor Click and Collect facilities. Great service means retaining well-trained staff, but alas, West End stores have about 110 per cent staff turnover per year on average.

Not so for John Lewis, where the cooperative structure of the organ- isation ensures well-above-average sales staff retention and, as a result, well-above-average sales results. No need for zero-hours contracts here: customers are prepared to pay a small premium for great service. Other brands need to pay attention in order to improve their West End service levels, which can be haphazard to say the least.

En route to peak tourism?

Overall tourist numbers in London increased by 26 per cent over the last five years, to over 18 million international leisure tourists per year.1 Their spending power is down, however, following an oil-price collapse that left the Russian oligarchs, middle-eastern Sheiks and Nigerian oil-princ- es out of pocket, and forcing luxury retail to shift its offer to a more middle-class price range. Only luxury cosmetics and food and drink have grown in volume, while luxury fashion and leather goods remain flat, reflecting higher volume but lower price due to less-affluent tourism.

Since 24th June, the added attraction of a low pound post-Brexit brings a new challenge to bricks-and-mortar outlets in the shape of

new, less-affluent Asian and European tourists, who are not big spend- ers but still love a lipstick from Selfridges or a scarf from Liberty.

They need to be made welcome and looked after like the previous luxury-hunting oil-ocracy, with more affordable hotels in the West End and mid-market shops to offer special (but not wallet-busting) cosmetics and service offers.

If this effect continues, shops will need to rethink their layouts to accommodate higher numbers of lower spenders. There are now many more ‘mid-wealth’ tourists than there were luxury-hunters, and the cos- metics floors at Selfridges and John Lewis already feel very cramped.

A new catalyst for increase in West End visitors is the Night Tube, used by 50,000 people on its first night on only the Jubilee and Central lines. It should bring £320m in new revenues to the West End over the next 20 years, increasing the number of jobs by about 2,000. It will also cut down evening traffic and pollution as people will not need to use their own cars.

The winners should be late coffee bars like Bar Italia in Soho, which, according to Google’s ‘popular times’ bar chart, is the only café in town where the peak traffic is at 2am on Saturday. The only problem is that there is only one Bar Italia so far … night-life lovers will need to bluff their way into private members’ clubs if in need of a late hideout.

Sadly, 15 London clubs have closed down in the last two years2 due to licensing problems, so it is not entirely clear where revellers are likely to go. At the time of writing, the number of licensed all- night venues in central London is lower than ever. Foursquare’s new venue-recommendation bot (called ‘Marsbot’) may help, but it will have a shockingly limited range of geo-suggestions to propose for a night crawl. Like 24-hour Tokyo, London’s West End will need many more all- night bars, 24/7 gyms and collaborative work places. Planners must get creative, or we will be all dressed up with nowhere to go after midnight.

Commercial challenges

The commercial market has bounced back from a peak of 9.2 per cent vacancies in 2009 (post-Lehman crisis) to 5.2 per cent in 2011 – and heading to less than 4.5 per cent today. Russian and Asian landlords seeking a safe haven have shown interest and now account for nearly 30 per cent of ownership.3 By comparison, less than 5 per cent of Tokyo and only 15 per cent of Paris are owned by foreign nationals.

As the pound weakens, there will be increasing demand from Asian investors, eager to buy a piece of heritage Britain. But despite new mon- ey pouring in, new space is forecast to increase by less than 1 per cent by the end of 2016,4 mainly due to outdated planning restrictions. The rest of the market’s activity is mainly driving an increase in prices, and therefore indirectly blocking innovation by making pop-ups and flexible collaboration spaces hard to find.

In terms of price, West End retail space is second in the world only to Manhattan. The only way young retail brands can get a presence in today’s West End is via tiny pop-ups in larger stores such as Topshop or Debenhams. There is no middle ground between an in-store mini-pop- up and a fully fledged flagship, due to a severe shortage of entry-level properties where young retailers can try innovative formats.

Large landlords are known to be highly risk-averse. If we want to keep future West End retail fresh and innovative, we need to address the record high rents, the impending upwards business rates review, the out- of-date planning policies, and the total lack of short-term leases. These are collectively creating boulder-sized stumbling blocks to the entry of new retail blood.

Managing density with technology

A significant upgrade of transport capacity is coming to the West End, with Crossrail beginning to call at Tottenham Court Road and Bond Street from 2018. It is expected that this will double the West End’s working population. With an increase in office workers, shoppers and tourists as a result of Crossrail and other travel trends, we need to manage available space in micro-units of time and rent-space. At the moment, footfall is measured by cameras, based on small samples and useful only as a broad guideline.

New measurement technology is emerging – from iBeacons to WiFi- based tracking of footfall – that offers a much better approximation in real time (and real space) of what happens outside each store, gym and office. The Local Data Company, in conjunction with University College London, is starting a pilot with an hour-by-hour, blow-by-blow data feed showing exactly how much traffic passes by each location.5

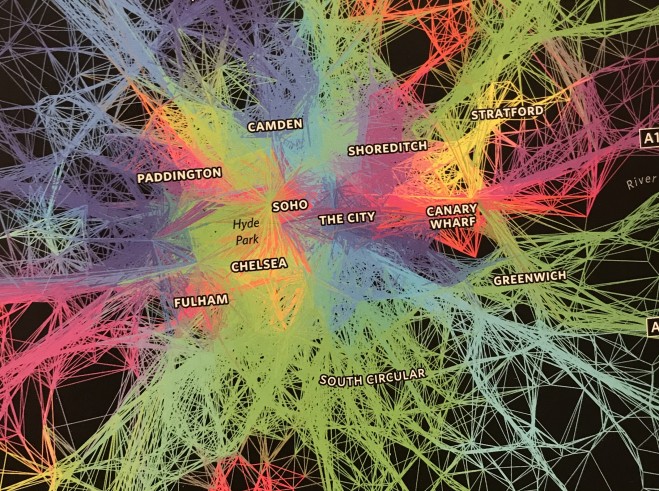

Additional research from Guy Lansley at University College London shows that it is possible to model an e-catchment area using metadata from Twitter (or, in future, Facebook, Instagram or Snapchat) to estab- lish how many people in a given office block are using a specific store. It will help to calculate, for example, a gym chain’s optimal locations in the area; or whether lunch pop-ups in flexible locations may be useful. And – despite its limitations of being skewed to more affluent and educated users – Twitter’s users could be a good proxy for the West End, as office workers in the area follow similar social network demographics.

With such analysis, we can begin to understand how high streets are used, how they are changing, and what drives footfall patterns in real time. It also offers the opportunity to unlock low-use time in retail and office space.

A company called Seat2Meet.com – a recent arrival in London from Holland – seeks to capitalise on the greater availability of information about usage in the West End. Already managing about 80,000 seats in locations across Europe, the company is helping restaurants to make use of their off-peak time by renting tables to business people who don’t need a full-day desk, but just a meeting table for a couple of hours.

With real-time information about availability of space, a growing army of young retail brands could take advantage of short-availabil- ity slots – perhaps in theatre foyers or hotel meeting rooms. Internet of Things-enabled micro-slot management will be the future of West End retail.

Meeting the future with innovation

Planners also need to become more responsive and recognise the pressures on space from expected future arrivals. Lego-like modules,

as created by the likes of Apex Airspace Developments, can be added

to flat roofs in the West End to create flexible spaces for a few years.

This allows occupants and landlords to test the waters, while supporting new retail formats and innovation in collaborative spaces. Gym on the top floor with rooftop views? Craft gin bar in the attic? All-night tattoo parlour above the offices? All and more will be needed to move the West End on so that it meets the needs of 24/7 millennials and their globalised business models.

Innovation is all about flexibility. But for start-ups, it is also about face-to-face meetings, suppliers coming into contact with potential business clients, the vibrancy and diversity of the West End supporting the wave of de-corporatisation, and the adjustment of thousands of professionals at the peak of their powers. The future may be beautiful, but it will be small, with agile and lean SMEs forming and re-forming in response to market needs. It will need flexible office space and low-cost retail pop-up spaces to thrive.

Tax incentives, alongside more flexible planning policies, can open up an agreed percentage of flexible, low-cost spaces for young inno- vators and collaborators. Once established, SMEs that succeed under Darwinian market pressures should be encouraged to continue in the West End. They will need office formats to suit the second and third phases of maturing companies – perhaps designated extra new-build floors on top of collab-rich buildings, which support an ecosystem of growing companies at every stage.

The only way for the West End is up. But it will take a lot more than wishful thinking to leverage the Night Tube and Crossrail investments, support new retail and office-space innovation, and remove pollution. Mayor Sadiq Khan is looking for a ‘Night Tsar’ to pull together busi- nesses, councils, transport and policing for London’s 24-hour economy. I think a ‘West End Tsar’ – who can dedicate undivided attention to making the area work for Londoners and tourists alike – should be next on his list.

Endnotes