Originally published on localdatacompany.org on 21 July 2017

On a sunny day back in May, we held our second ‘Retail Leaders’ Forum’ event in conjunction with the SaïdBusiness School in Oxford. These events are held bi-annually and are designed to provide an environment for current and future leaders in retail to share challenges and best practice in how they use data to drive their businesses forward.

This year, we had representatives from some huge names including British Land, LEON, Tesco, Clarks, Dixons Carphone, Mitchells and Butlers, PwC, University College London, the University of Oxford and many more. The level of debate was exceptional this year, with retail practitioners and academics coming together to talk about the challenges they are currently facing, and calling on the group to share and solve common problems.

The second session of the day, focused around ‘Places’ was facilitated by Emma Clarke, Head of UK Property Research at Tesco and Dr. Jonathan Reynolds, Academic Director at the Oxford Institute of Retail Management, University of Oxford. In this session the group were asked to focus on a few key points, these being: what data can tell us about places, what they thought were the important emerging variables when analysing places, what complexities they came across when modelling contemporary catchments and the new ways places were changing, interacting or competing. The below is an overview of just a fraction of the discussion between the delegates, facilitated by Emma and Jonathan.

Image 2: Emma Clarke of Tesco at the Retail Leaders’ Forum (Source LDC)

The first point made by our delegates in the discussion was that the context of a place is key to understanding it fully. Where it lies, both within the UK and within the network of other places that surrounds it can go a huge way to understanding how to improve its performance. Places should not always be seen as standalone destinations as they can work together to meet consumers’ needs. It is also key to understand how places interact with public space and transport links, as this can hold the key to success.

Another key element to understanding places is establishing their use and the shopper mission they meet. There has been much talk over the past few months around the difference between experiential vs transactional shopping missions, with the experiential locations often being viewed as more desirable. However, both of these location types have their place in consumers lives, as expectations for a day out to a shopping centre are totally different to expectations of nipping into a homeware store for paint when you’ve run out, or milk when you get back from a holiday. Places need to decide what they want to be known for and they need to play to their strengths. Places can’t be all things to all people.

Image 3: Delegates debating during the session. (Source: LDC)

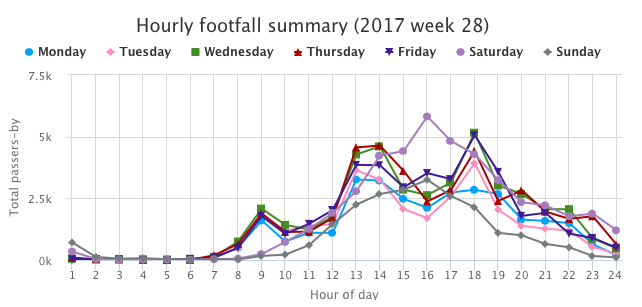

Where stores are located and what they offer also needs to be closely aligned to the demographic of the catchment and the needs of that demographic, an idea which was not new or revolutionary to any of the group. However, advancing technology and insights are enabling retailers to be much more exact and pitch-orientated. The delegates discussed the relevance of footfall data and how this is becoming increasingly valuable to them. Within any major city or large town, there are likely to be many different groups of people all using the centre in a variety of ways. It is therefore valuable to quantify opportunity and trends within micro-locations in a large centre. Footfall data helps us to identify hot-spots at street level and we can use trend profiles give a strong indication of shopper mission.

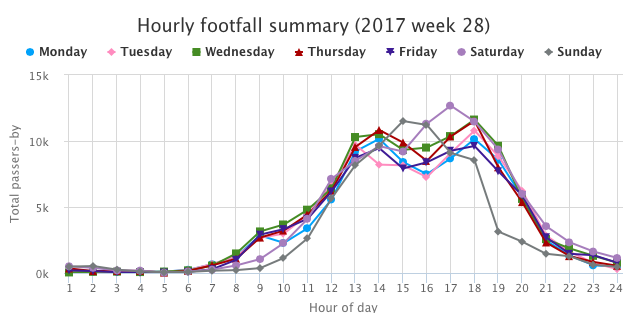

As an example of this point, see below two footfall graphs which both show streets in Manchester. Figure 1 shows data for Market Street, which is one of Manchester’s main retail thoroughfairs, known mainly for a high level of Comparison (non-food) retail. From the graph you can see a real lean towards afternoon footfall, which is typical of locations with a high number of stores of this type.

Figure 1: Footfall data for Market Street, Manchester. (Source: LDC)

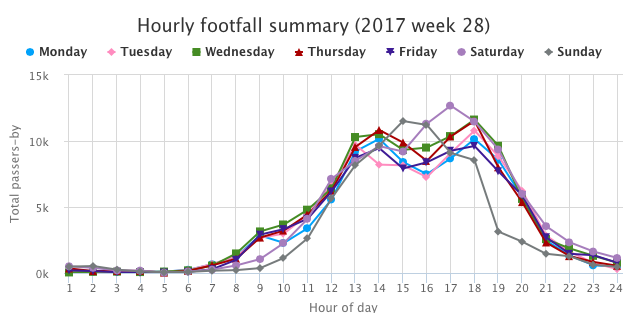

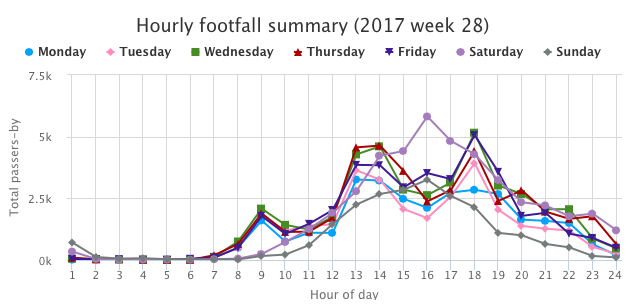

Figure 2 below shows a very different profile albeit in the same city. Footfall data for King Street shows a typical workforce curve, as you can see by the peak from 8-10, during lunch hour and dinner/evenings. That being said, unlike some locations with a similar trend curve, say in London, there is still footfall at weekends and this is largely driven by a premium retail offer in this area.

Figure 2: Footfall data for King Street, Manchester. (Source: LDC)

Our delegates were excited about how they might use this type of granular insight into shopper behaviour, and how it could help them to gain insight into the micro-level shopper missions. They talked about using this data to plan their locations with a higher level of accuracy, being able to identify streets that would be more relevant to their concept.

Now that there is so much data available on places, one thing that everyone at the forum had in common was the desire to collaborate. Delegates at the event urged each other to share their data and work together to support British retail. They saw a future in which occupiers, landlords and local authorities were working together to improve places for everyone. This brought the group on to the question ‘Are Britain’s high streets fit for purpose?’. How can they still appeal to shoppers with the parking and access issues and small unit size that seem to only be able to attract hair and beauty salons and charity shops? Should we make way for retail parks and mega malls instead? What can be done to ensure that a full retail mix remains present on our high streets?

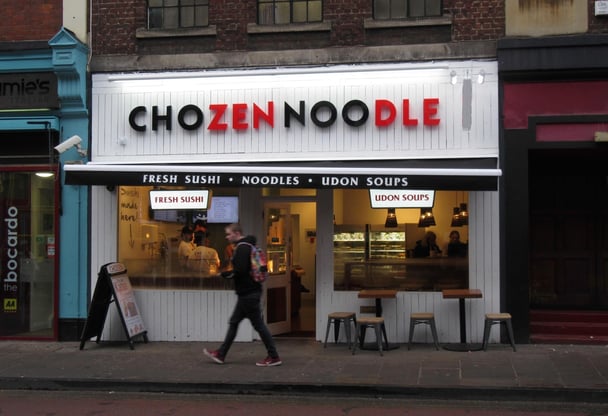

These questions don’t have a simple answer. One suggestion from our delegates was whether using physical stores for multiple purposes would reduce the pressure of surviving purely on physical sales alone. With popularity of click and collect services increasing, many physical stores could be used as collection points, with shoppers picking up a few extra bits as they come to collect their online purchases. This is also a relevant issue for leisure occupiers, who feel the pressure from services such as Deliveroo and Just Eat. However, the food delivered by these services must still be prepared in a location that will be quick to arrive with consumers spread across cities and towns in the UK. Leisure businesses with physical premises should consider how they can support these delivery services and supplement their revenue, rather than fight against this trend. However, physical stores will need to be clear on their strategy for this, who will get served first, the customer who has been waiting in the store to be served for 20 minutes in store, or the Deliveroo driver who has to get an order to the consumer quickly.

Image 4: Chosen Noodle take away shop, Oxford. (Source: LDC)

The session finished with a discussion around the difficulty of collecting comprehensive trend data for places, as this often comes from many different sources. Our delegates once again called on collaboration from parties, including academic partners, to aggregate the data from many sources, to build one, rich picture that can produce actionable insights. Collaboration was certainly a theme for the entire day, not just this session on people. We’ll bring the highlights from the rest of the session to you another day.

Our next Retail Leaders Forum will be held in May 2019, and we look forward to reviewing how our practitioners have moved on from these issues, and what new challenges they face in a retail landscape that I have no doubt will change significantly over the next 18 months or so.